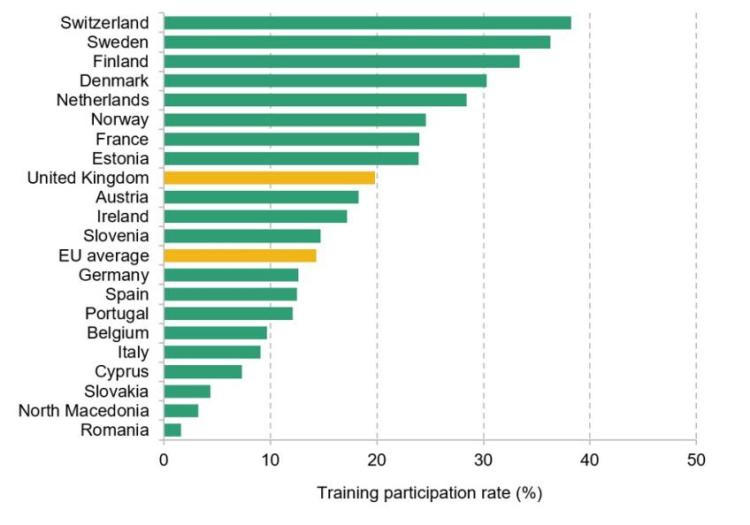

The UK has seen a significant decline in investment in adult education and training. This chapter analyses how the skills system should be reformed.

Key findings

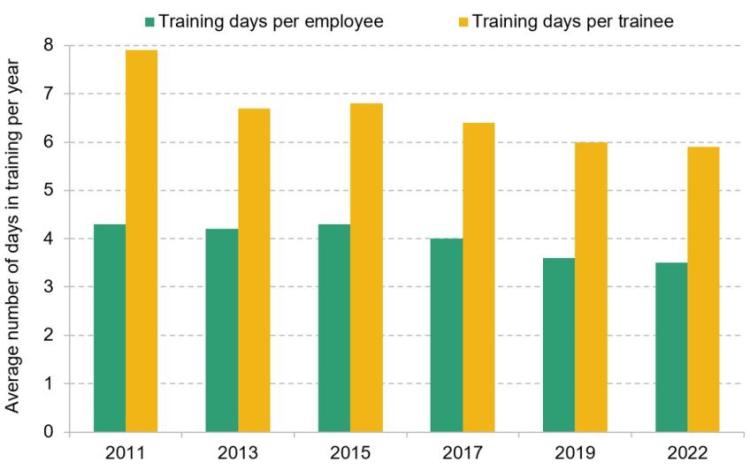

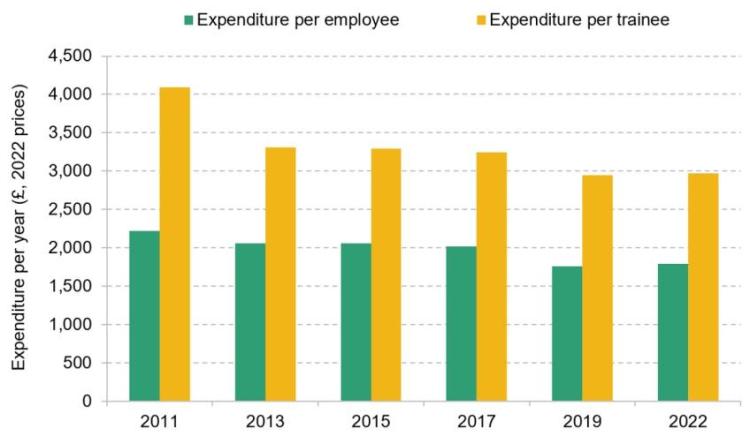

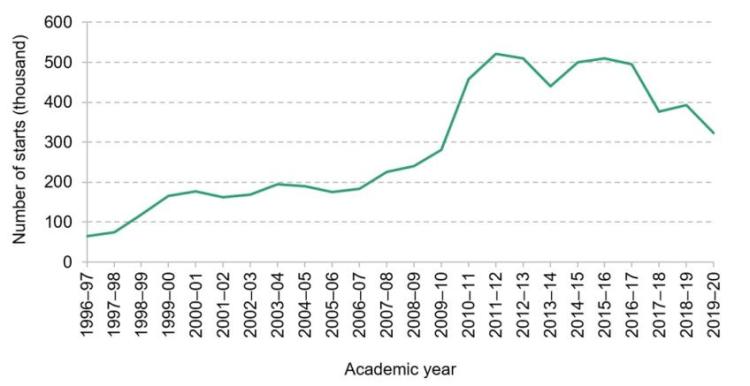

1. The UK has seen a significant decline in participation in adult education and training. The number of publicly funded qualifications started by adults has declined by 70% since the early 2000s, dropping from nearly 5.5 million qualifications to 1.5 million by 2020. Although the total number of adults participating in employer- provided training has remained fairly stable over time, the average number of days of workplace training received each year has fallen by 19% per employee in England since 2011.

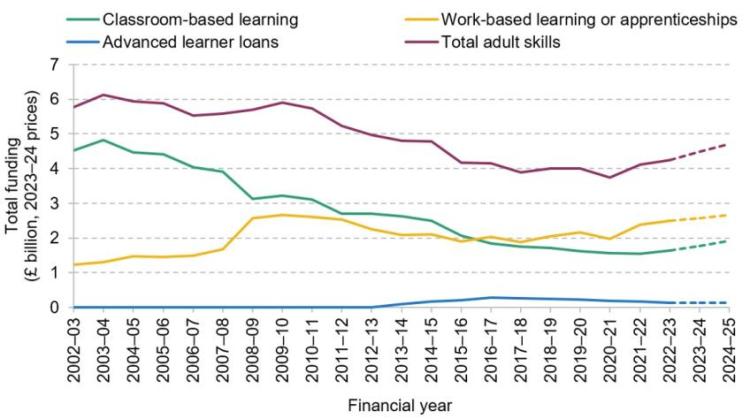

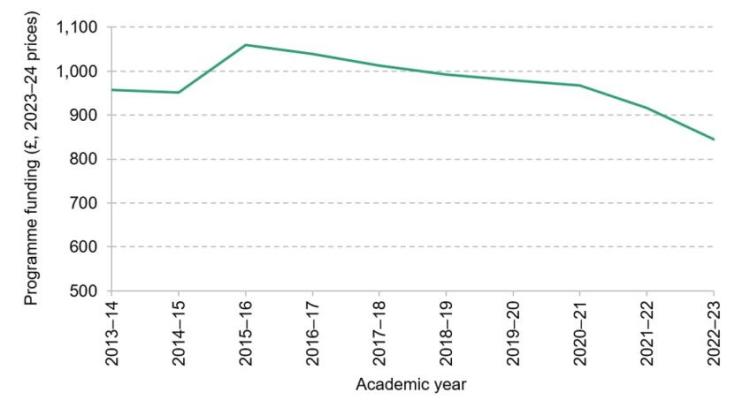

2. The decline in training participation has occurred alongside a fall in both public and private investment in training. Average employer spending on training has decreased by 27% per trainee since 2011. Since its peak in 2003–04, public funding for adult skills has fallen by 31% in real terms, mostly as a result of a reduction in provision of low-level courses. But the historical decline in funding also reflects long-term freezes in funding rates. Funding provided for an adult learner taking GCSE English or maths has fallen by 20% since 2015–16 in real terms.

3. There are five main policy levers that this (or a future) government might look to in the adult skills policy sphere: the direct public funding of qualifications and skills programmes, loans to learners, training subsidies, taxation of training and the regulation of training. In making changes to any lever, there is a trade-off between the costs of the reform (both the fiscal cost and the cost associated with further policy churn) and the benefits, which depend on whether the reform leads to additional training that is genuinely new and productive.

4. Ensuring that public funding of adult education is well spent is key. Adult skills funding is set to increase by 11% on today’s levels, reaching around £4.7 billion by 2024–25. Given the low returns to many adult skills courses, instead of expanding the range of courses that are publicly funded, the government might more helpfully review whether increasing existing funding rates would offer a better return.

5. The student loans system is set to be reformed with the introduction of the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE), which will merge the two separate loan systems that currently exist for further and higher education. In 2022–23, the amount lent to further education students (£124 million) was less than 1% of the amount lent to higher education students (£19.9 billion). The LLE has the potential to reshape the post-18 student loan landscape. However, progress in implementing the LLE has been slow. And important questions still remain about how the system will be designed, including which courses will be covered by the new loan entitlement. The government should provide clarity on the design of the LLE and ensure that it moves forward with its implementation within a reasonable time frame.

6. The government introduced the apprenticeship levy in 2017 as a means to deliver 3 million apprenticeship starts in England by 2020. This target was not met, with around 2 million apprenticeship starts between 2015 and 2020. While overall numbers of apprenticeships have fallen back, the number of higher-level apprenticeships has almost tripled since 2016, and the average duration of apprenticeships has increased by 22%. Since the apprenticeship levy was introduced in 2017, it has raised £580 million more than has been allocated for spending on skills and training across the UK.

7. The apprenticeship levy should be reformed to have a uniform subsidy rate for all employers. Currently, levy-paying employers (who tend to be bigger) benefit from a higher subsidy rate. While there is a case for subsidy rates being set according to the degree to which training is likely to be underprovided, this would be complicated and difficult to measure and implement in practice, so a uniform rate is desirable. The uniform subsidy rate should also be set at a lower level than the current rates which effectively subsidise the full cost of apprenticeship training.

8. The Labour party has announced plans to broaden the apprenticeship levy into a ‘growth and skills levy’, which will allow employers to use subsidies for non- apprenticeship training. Past experience, with schemes such as Train to Gain in the late 2000s, suggests that there is a risk of significant deadweight costs (i.e. subsidising training that would have taken place anyway). In addition, an extended subsidy would add to costs, which could perhaps be covered by lowering the existing subsidy rates.

Chosen excerpts by Job Market Monitor. Read the whole story @ Investment in training and skills | Institute for Fiscal Studies

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your insightful blog post. Your perspectives and ideas were incredibly helpful.

Posted by First Demat | January 29, 2024, 5:55 amI greatly enjoyed reading your blog post. Your insights were incredibly helpful, and the way you presented them really resonated with me. It was a perspective I hadn’t considered before, and it truly made a lot of sense.

Posted by First Demat | January 29, 2024, 6:09 am