As many countries complete the demographic transition, their populations age. While a growing working-age share thanks to aging has been a source for economic growth, contracting working-age shares now threaten to turn the former demographic dividend into a demographic drag.

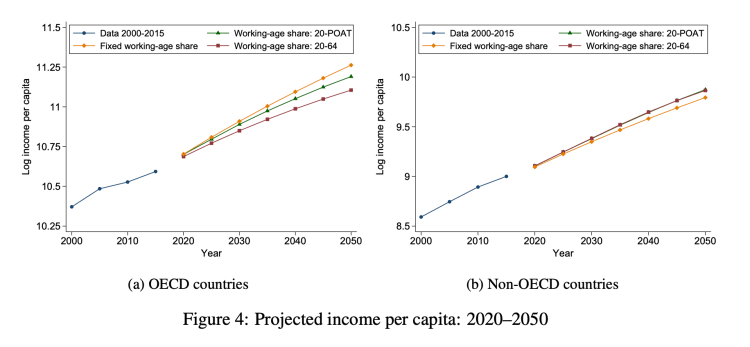

In this paper, we investigate the consequences of changes in working-age shares for economic growth. We develop an aggregate production model and fit it in a dynamic panel for 1950–2015 to project income per capita in 2020–2050. The novelty of our approach lies in the distinction between retrospective and prospective concepts of population age structure, which allows us to gauge the extent to which population aging might slow economic growth as large cohorts pass through to older ages and to determine by how much extensions of working ages with improvements in functional capacity can counteract this slowdown.

Our findings document that a demographic drag will be the new norm in the upcoming decades; however, future economic growth depends not only on how cohort structures change but also on how labor potential changes with improvements in functional capacity as longevity rises. While contracting working-age shares will slow economic growth, changes in labor supply through improvements in functional capacity can cushion much of this slowdown. Hence, the consequences of population aging for economic growth will likely be less severe than demographic predictions of cohort structure suggest. Although migration and technological progress can reduce the demographic drag by cushioning labor shortages, automating physically demanding tasks, and creating age- friendly jobs (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2017, 2022; Acemoglu et al. 2022), they will be insufficient to counteract the demographic drag alone. In this context, our findings indicate substantial gains forpolicies that enable older people to remain economically active, including productive nonmarket activities (Bloom et al. 2020). While higher functional capacity tends to increase people’s propensity to work full time at older ages, it need not raise labor force participation (Appendix A.9). Whether such an increase occurs depends on the extent to which labor markets and health and social policy facilitate retaining workers in the workforce. Potential policies along these lines include creating incentives for remaining in employment, promoting safe workplaces, providing access to an adequate safety net regarding healthcare and retirement, reducing social inequalities conducive to ill health, and meeting people’s needs in dealing with caregiving responsibilities (Berkman et al. 2022).

We conclude with four cautionary remarks. First, projecting the effects of population aging on economic growth involves considerable uncertainty. Among other things, it is difficult to reliably predict the occurrences of technological innovations, climate change, pandemics, and war and their impacts on per-capita income and its growth rate. Economic growth may well be slower than in the past (Gordon 2015). Therefore, we view our projections not as forecasts of economic growth but as estimates of the economic implications of global population aging trends based on available information and economic conditions today. Second, our results rely on the assumption that prospective measures of population aging reflect variation in age-specific functional capacities. While our evidence confirms that this is the case, we cannot rule out the possibility that alternative measures capture this variation more effectively. So far, potential alternatives such as function-based dependency ratios (Skirbekk et al. 2012, 2022) and healthy life expectancy (Vos et al. 2020) do not offer straight-forward approaches to modeling the economic gains associated with expansions of labor potential due to changing age patterns of health. How different measures of prospective aging and functional capacity compare with one another is a fruitful avenue for future research. Third, our analysis is silent with respect to the fiscal implications of population aging. A rising number of elderly people can pressure the adequate provision of pensions, healthcare, and long-term care (Rouzet et al. 2019), which might necessitate an increase in taxes that further slows economic growth. In theory, extending economic activity into older ages can absorb fiscal strain from social security systems and cushion this effect. Fourth, our analysis abstracts from distributional differences in economic activity around old-age thresholds. Because this abstraction accurately represents average functional capacity, it is inconsequential for projected growth of income per capita. Nevertheless, policies aimed at expanding economic activity into the older ages can have distributional and related welfare implications. Measuring this effect is a worthwhile area for future research.

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: Aging Societies – They rely on immigrant for health-care workers while the world is short on them | Job Market Monitor - March 7, 2024