In January, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics significantly reduced its projections for medium-term labor force participation. The revision implies that recent participation declines have largely been due to long-term trends rather than business-cycle effects. However, as the economy recovers, some discouraged workers may return to the labor force, boosting participation beyond the Bureau’s forecast. Given current job creation rates, if workers who want a job but are not actively looking join the labor force, the unemployment rate could stop falling in the short term.

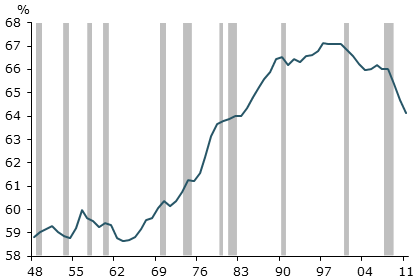

Roughly every two years, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes medium-term labor force projections that reflect its views on labor force participation and population growth. The BLS’s January 2012 release included significant downward revisions to earlier labor force projections. The revisions mostly reflected lower projections of the percentages of young and prime-working-age people likely to be working or looking for work in coming years. Behind this outlook lies an important assumption. The BLS attributes much of these groups’ recent declines in labor force participation to ongoing secular trends rather than to transitory effects of the recent economic downturn. This Economic Letter assesses this view and examines how alternative participation projections might affect the unemployment rate in the years ahead…

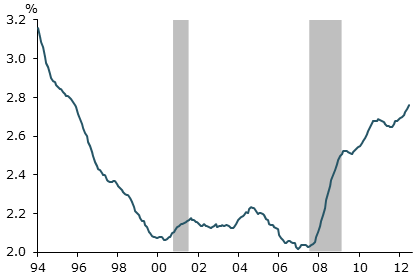

the BLS has interpreted most of the recent reduction in labor force participation as a secular change in trend rather than a transitory decline. One way to assess whether this projection will be accurate is to look at survey data from the monthly Current Population Survey (CPS). Each month the survey asks individuals in a representative sample of U.S. households whether they are working, looking for work, or out of the labor force. Since 1994, the survey has asked those who say they are out of the labor force whether they currently want a job. Figure 2 plots the number of working-age adults outside the labor force who say they want a job as a percentage of the total noninstitutionalized civilian population 16 and older. Gray bars indicate recessions.

As the figure shows, the current share of the adult population that is out of the labor force but wants a job is elevated, but not unusually so by historical standards. In the previous expansion, from December 2001 through November 2007, an average 2.1% of the population wanted a job but was not in the labor force. This share rose sharply starting in 2008. Currently it is 0.7 percentage point above the average level from 2001–07, nearly matching the 0.8 percentage point cyclical shortfall implied in the BLS January 2012 projections. Based on these numbers, the BLS projections appear well-aligned with the historical behavior of people marginally attached to the labor force.

Nearly 6.9 million people report being out of the labor force but wanting a job. As economic conditions improve, it is reasonable to expect that some of these workers will move back into the labor force or join for the first time. Based on historical averages, about 2.1 million of them could enter the job market. These potential entrants will either take jobs directly or join the labor force as unemployed workers actively searching for jobs.

The near-term path of unemployment will reflect both how quickly potential workers enter the labor force and the rate at which jobs are created. Assume that the average pace of job creation over the past two years continues. We can then project the path of the unemployment rate over the next year according to the rate at which the 2.1 million potential workers enter the labor force.

If these workers take a year and a half to join the labor force, which would be about a year faster than the entry rate from 1994 to 1999, the recent decline in the unemployment rate would stall at more than 8% by the end of next year. Suppose though that the number of workers who want a job but are not actively looking falls at a more moderate pace and it takes three-and-a-half years for this group to join the labor force. In that case, the unemployment rate would stay at 7.7% through the end of next year. For comparison, if none of the 2.1 million potential workers were to enter the labor market, the unemployment rate would fall to 7.4% by the end of 2013. Of course, the rate at which these workers join the labor force may reflect the labor market’s overall strength. A faster rate of job creation may offset a faster rate of labor force entry, allowing the unemployment rate to fall.

Choosen excerpts by Job Market Monitor from

via FRBSF Economic Letter: Will the Jobless Rate Drop Take a Break? (2012-37, 12/17/2012).

Related Post

Srinking Labor Force | Women are pouring out of the job market

Among the new employment figures the Labor Department released Friday morning is an obscure one that’s ripe for politicking: the labor force participation rate. It measures the percentage of the population age 16 and above who are actually working. The labor force participation rate fell last month to 63.6 percent, its lowest level since 1981. … Continue reading »

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: How Long Will it Take to Get to 6.5 Percent Unemployment? | Brookings Institution « Job Market Monitor - December 17, 2012

Pingback: US – 9.6 Percent of families included an unemployed person in 2013 finds the BLS | Job Market Monitor - April 30, 2014

Pingback: US – The state of the labor market in figures | Job Market Monitor - May 2, 2014