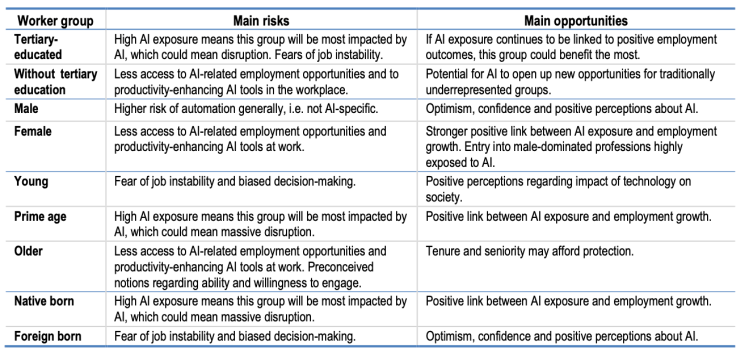

This paper examines how different socio-demographic groups experience AI at work. As AI can automate non-routine, cognitive tasks, tertiary-educated workers in “white-collar” occupations will likely face disruption, even if empirical analysis does not suggest that overall employment levels have fallen due to AI, even in “white-collar” occupations. The main risk for those without tertiary education, female and older workers is that they lose out due to lower access to AI-related employment opportunities and to productivity-enhancing AI tools in the workplace. By identifying the main risks and opportunities associated with different socio-demographic groups, the ultimate aim is to allow policy makers to target supports and to capture the benefits of AI (increased productivity and economic growth) without increasing inequalities and societal resistance to technological progress.

AI has made most progress in automating non-routine, cognitive tasks. Many of the occupations most exposed to AI (including the latest developments in generative AI) are therefore “white-collar” occupations typically requiring several years of formal training and/or tertiary education, e.g. IT professionals, managers, and science and engineering professionals. Occupations which rely on manual skills and strength, such as cleaners, labourers and food preparation assistants, tend to have low AI exposure.

As a result, education is an important determinant of AI exposure. Occupations highly exposed to AI not only have a large proportion of highly educated workers, but education also mediates the relation between AI exposure and other socio-demographic characteristics. Native-born and prime-age workers can be considered among the groups most exposed to AI, partly because they tend to be in occupations with higher educational attainment. Female and male workers face roughly the same occupational exposure to AI overall.

Occupations with the highest exposure to AI will be most impacted by AI and could face the most disruption. While AI advances are emerging in fast succession, analysis of historical data does not suggest that AI exposure has led to negative employment or wage outcomes on aggregate so far.

Some studies even suggest that AI exposure has been linked to positive outcomes and that these links have been stronger among more educated and higher-income workers, potentially deepening existing inequalities.

New analysis reinforces the idea that there was a positive relationship between AI exposure and

employment in the period from 2012 to 2022. It shows that:

• Both female and male employment are positively related with AI exposure, when controlling for

other technological advances, offshorability and international trade as well as for trends at

occupation and country levels. Women’s employment growth was even higher than men’s in

occupations highly exposed to AI, which can be interpreted as a continuation of the trend of

declining occupational gender segregation, i.e. women’s entry into traditionally male-dominated

occupations and vice versa. Examples of occupations highly exposed to AI in which female

employment has grown include chief executives (32% to 39% female between 2012 and 2022) and

science and engineering professionals (31% to 35%).

• The relation between AI exposure and employment growth for prime-age workers and for

native-born workers is also positive, suggesting that employment of these groups has either grown

more or reduced less in occupations more exposed to AI (countering trends observed in the

working population on the whole).

• There is little to suggest that, so far, exposure to AI has led to different outcomes for different

demographic groups in terms of usual working hours or wage growth.

Some groups have greater access to opportunities associated with AI, which could prevent the benefits of AI from being broadly and fairly shared. Male workers with a university degree are overrepresented in both the AI workforce (the narrow set of workers with the skills to develop and maintain AI systems) and among AI users (workers who interact with AI at work). Consequently, women and lower-educated workers could have less access to AI-related employment opportunities and to productivity-enhancing AI tools in the workplace. At the same time, if used correctly, some features of AI could open up new opportunities for traditionally underrepresented groups.

Interviews with workers on the topic of AI reveal the hopes, expectations and worries of different groups.

Male, university-educated and foreign-born workers tend to have more positive perceptions of AI,

according to an international survey of workers undertaken in early 2022 in the manufacturing and finance sectors. These groups were more likely to say that AI had improved their productivity and working conditions, that AI would increase their wages in the future, and that they were enthusiastic to learn more about AI. The same groups (along with younger workers) were also more likely to agree that technology had an overall positive impact on society. Despite this, university-educated workers were more likely to say that they were worried about job loss due to AI in the following 10 years (primarily because this group were more likely to be AI users). Foreign-born workers and younger workers were also more worried about job loss due to AI in the following 10 years and more worried that data collection would lead to decisions biased against them.

Case study interviews conducted in parallel suggest that young and older workers are facing different risks.

Older workers face preconceived and potentially even prejudicial notions regarding their ability and

willingness to engage with new technologies. On the other hand, their tenure and seniority may afford them greater protection from job loss than younger workers.

Table: Synthesis of the main risks and opportunities pertaining to each socio-demographic group

The synthesis of main risks and opportunities may allow policy makers to think about how to target different supports as to capture the benefits of AI (increased productivity and economic growth) without increasing inequalities and societal resistance to technological progress. For instance, programmes aimed at upskilling and empowering workers to use AI may be best targeted to those without tertiary education, to women and to older workers. Even if AI exposure has traditionally been associated with positive employment outcomes, some tertiary-educated workers will require support to overcome disruption and allow them to transition to new jobs. Policy makers will want to ensure that AI is used in a trustworthy manner, that it is not being used to perpetuate historical patterns of disadvantage, and that the benefits from AI are broadly and fairly shared.

Chosen excerpts by Job Market Monitor. Read the whole story @ Who will be the workers most affected by AI? | OECD

Discussion

No comments yet.