Human capital is the most important component of total wealth, where total wealth is defined as the sum of produced capital (both tangible physical capital and intangible knowledge capital), natural capital and human capital. Total wealth represents the capacity to generate and increase a future income level that is sustainable. For example, an increase in total wealth per capita arising from an increase in female labour force participation, an increase in the education level of women or an increase in the earnings of women signals a high level of future income for a nation. On the other hand, a decline in total wealth per capita arising from a decline in human capital because of aging signals that the current income level may not be sustainable if that decline is not accompanied by an increase in other forms of assets, such as physical capital or knowledge capital.

This paper provides a gender analysis of human capital and examines the contribution of women to the level and growth of human capital in Canada from 1970 to 2020. While the estimates cover 1970 to 2020, the 2020 estimates will be presented separately to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on human capital. Human capital is estimated using the income-based approach of Jorgenson and Fraumeni (1989, 1992), and it is calculated as the present discounted value of future labour income of individuals over their working life.

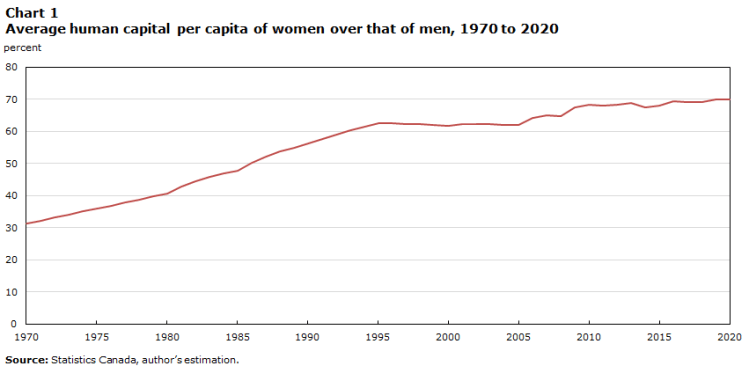

The average human capital of women was lower than that of men. However, the gender gap in human capital declined over time as a result of the relatively faster growth of human capital among women, which arose from large increases in the labour force participation, education level and earnings of women compared with those of men. In 1970, there was a large gap in human capital between women and men, and the average human capital of women was 35% of that of men. This large gap reflects lower labour force participation, fewer hours worked and lower hourly earnings for women. By 2020, the average human capital of women reached 70% of that of men.

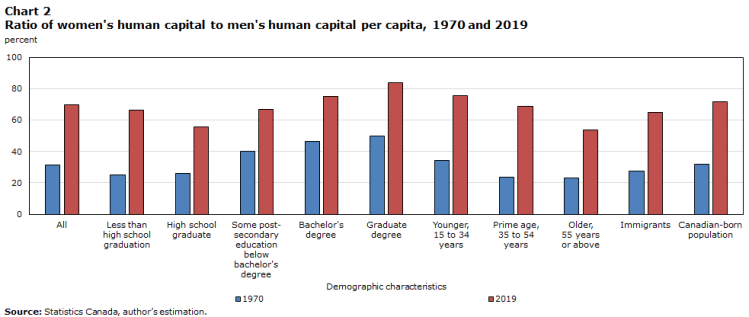

Gender gaps in the average human capital between men and women existed among all age groups and education levels. All the gaps have narrowed significantly—especially for prime working age women, aged 35 to 54 years old—since 1970.

The gender gap in human capital was larger for immigrant women than for Canadian-born women. In 1970, the average human capital for immigrant women was about 31% of that of immigrant men, while the average human capital of Canadian-born women was about 36% of that of Canadian-born men. Over time, the gender gap narrowed at a similar pace for both immigrant and Canadian-born women. By 2020, the average human capital of immigrant women was 66% of that of immigrant men, while the average human capital of Canadian-born women was about 71% of that of Canadian-born men.

Relatively large gender gaps among immigrants existed for almost all age groups and education levels, especially for immigrant women with a high school education or below. The gender gap narrowed at a similar pace for both immigrants and Canadian-born individuals. Before the mid-1990s, its decline was faster among the immigrant population when compared with the Canadian-born population; its decline was slower after the mid-1990s.

As a result of rapid growth in human capital among women, the share of total human capital accounted for by women rose from 30% in 1970 to 41% in 2020. The increase in that share was much faster before the mid-1990s because of large increases in women’s labour force participation. From 1970 to 1995, the share of human capital of women rose from 30% to 39%. From 1995 to 2020, the share increased from 39% to 41%.

Women accounted for a disproportionately large portion of the growth in human capital over time. However, women’s contribution to aggregate growth in human capital declined after the mid-1990s because of a decline in the relative growth in human capital for women during the same period. Before 1995, women accounted for about 58% of the growth in human capital, which was larger than their share of human capital (33%) during that period. From 1995 to 2020, women accounted for 45% of the growth in human capital, while their share of human capital was 40%.

Both immigrant women and immigrant men have increased their contribution to human capital growth over time. After 1995, immigrants accounted for about 40% of the growth in human capital—56% of which may be attributed to immigrant men and 44% to immigrant women. Before 1995, immigrants accounted for about 18% of the growth in human capital.

Discussion

No comments yet.