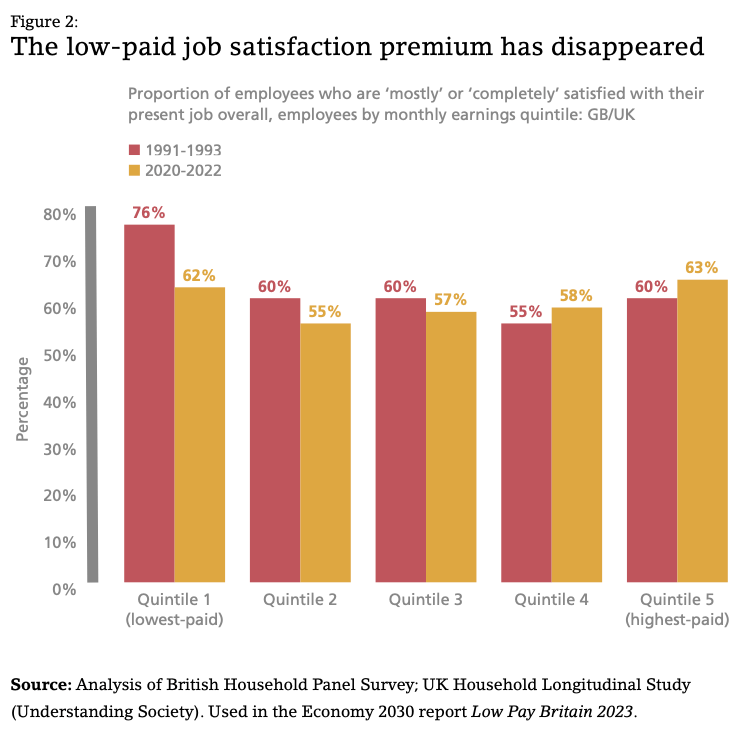

Good work is key for people’s sense of wellbeing. This month’s CentrePiece cover story reveals how conditions for the lowest-paid workers have been eroded, despite the success of the national minimum wage. The priority now must be to provide a broad-based platform for treating lower earners with dignity.

The ramping up of the national minimum wage since 2015 has more than halved the share of low-paid employees in Britain. But it is far from job done: too few low-paying jobs offer dignity, respect and security to the people doing them. Nye Cominetti, Rui Costa, Charlie McCurdy and Gregory Thwaites report on how the minimum wage has transformed pay – and how we can go beyond this to make real progress on providing ‘good work’.

Too many low-paying jobs do not offer good work

Work means very different things to lower and higher earners: not enough of the former enjoy the basics of dignity, respect and security that the latter take for granted. We should care about good quality work because it matters for workers’ lives and wellbeing.

While there is no single thing that makes a job “good” or “bad”, we can confidently list as “good” such qualities

as security, autonomy, having a voice in the workplace and opportunities for progression. Volatile pay, intense work or a lack of certainty over when you work are “bad”.

These aspects of job quality are distributed very unequally. Workers who are in the lowest fifth by hourly pay are more than twice as likely as workers in the highest-paid quintile (38% compared with 15%) to say they have little or no autonomy at work; almost four times as likely to experience volatility in their hours and pay (22% compared with 6%); and four times as likely to be working fewer hours than they would like (17% compared with 4%).

There are large geographical differences in unfavourable job characteristics

An analysis of Office for National Statistics data shows that at the local authority level, over half of employees have no good opportunities for progression in the likes of Dudley (56%), Sunderland (56%), Barnsley (55%) and Wolverhampton (55%). This is around twice the rate of London boroughslike Barking and Dagenham (29%), Islington (28%) and Tower Hamlets (28%).

A ‘good work’ agenda must provide a broad-based platform for treating lower earners with dignity

Pay is clearly important for quality work. But other aspects of work such as security, autonomy and dignity clearly matter a lot as well. Half of private sector employees say they would be willing to turn down a pay rise for a range of improvements – some boil down to working less for the same pay (including workers who want more holiday or to work fewer hours), but some are completely separate from pay, including workers who want work to be more meaningful or to be treated with more dignity at work.

What concretely would a platform that aims to make progress look like? The priority areas would be sick pay, hours and pay volatility, and unfair dismissal, each of which can be broadly seen as policies relating to security at work. On sick pay, we must improve the level of SSP and make it universally available. We propose an earnings replacement approach, where SSP is paid at 65% of a worker’s usual earnings (close to the median OECD replacement rate over a four-week sickness absence of 64%). And the number of waiting days should be reduced from three to one – meaning that workers would receive SSP from the second day.

Discussion

No comments yet.