Summary

Developing digital – or ICT – skills has been a policy priority in the past years, given rapid technological change in sectors and occupations. But the contribution of digital skills goes far beyond this. Digital skills are an enabler of citizenship in societies and a driver of efficient and just green and digital transitions. Beyond particular sectors and occupations (e.g. ICT techniciansand ICT professionals) which develop and provide digital goods and services, digital skills are increasingly becoming a transversal requirement in all occupations and sectors.

The Covid-19 pandemic and its wide-ranging impacts have accelerated digital skills demand in many occupations, especially non-ICT ones. Effective use of digital skills proved to be a driver of resilience. They help workers and entire organisations adapt to the new realities the pandemic has shaped. Particularly in retail and service sectors, where it is difficult to deliver products and services remotely, digital skills can spur the transformation of business models and help avoid lay-offs and bankruptcies. Digital skills also enabled continued provision of public and private services. Thanks to them, many workers for whom digital skills were not critical before the pandemic (for example teachers, clerical and other office jobs), could shift to remote working basically overnight.

The growing importance of digital skills and knowledge in online job advertisements in the course of 2020 is a sign of progressing workplace digitalisation. Demand for knowledge of business ICT systems and applications, tools for software and web development and configuration and for data analysis accounted for roughly half of the growth in skills demand. The growing workplace digitalisation, once ingrained into organisations’ business models and customer behaviour, may become permanent, even after the pandemic subsides. And while some jobs unaffected by digital technologies will remain, digitalisation will continue to shape skills, tasks and jobs.

Strengthening digital competences is a priority area for both EU Member states and candidate countries. While there are many activities focusing IVET learners, much work remains to be done in CVET, to close the digital skill gap of adults. In addition, training teachers and trainers in digital competences so that they can effectively support learners is an underdeveloped area in many national skill systems. Technological innovation and digitalisation have the potential to transform learning fundamentally – not only by equipping the population with digital skills to work and be active citizens, but also by improving access to learning, as the Covid-19 pandemic has shown us.

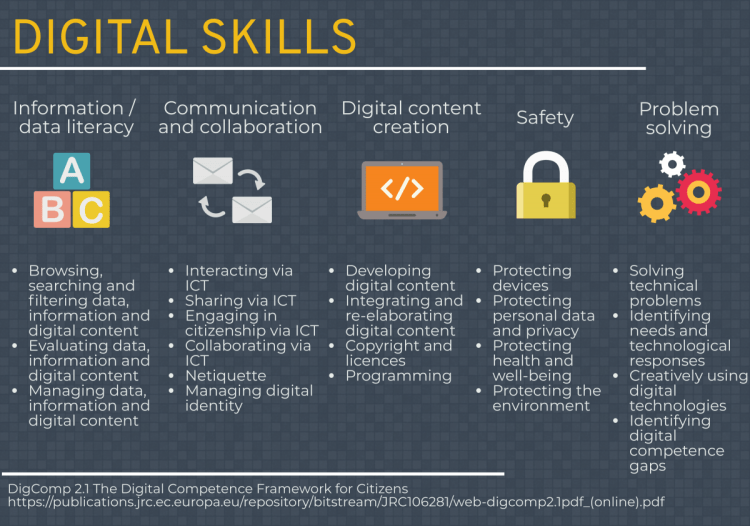

What are digital skills?

Under the digital skills umbrella five types of skills can be distinguished:

- information processing (e.g. using a search engine and storing information and data);

- communication (including teleconferencing and application sharing);

- content creation (such as producing text and tables, and multimedia content);

- security (e.g. using a password and encrypting files); and,

- problem solving (e.g. finding IT assistance and using software tools to solve problems)[1].

Figure 1: The digital competence framework for citizens

Source: DigComp 2.1 The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC106281/web-digcomp2.1pdf_(online).pdf

The diffusion of digital technologies drives transformation in the world of work. New types of jobs are emerging and routine-based jobs are disappearing. Specialised ICT profiles and higher ICT skills are increasingly required in many occupations, and all citizens need at least basic digital skills to participate in society ([2]). The EU’s Digital Education Action Plan ([3]) puts digital skills development centre stage.

Digital divide in the EU

Promoting access to high-quality digital skills training for all workers and citizens has been a top policy priority. To understand where countries stand in terms of digital skills and to monitor their progress, the level of mastery of digital skills is one of the most used indicators. Apart from measuring the extent to which people can use digital technologies, digital skills indicators also help gain insight into the type of jobs or careers they can pursue, and the barriers they face at work and in life ([4]).

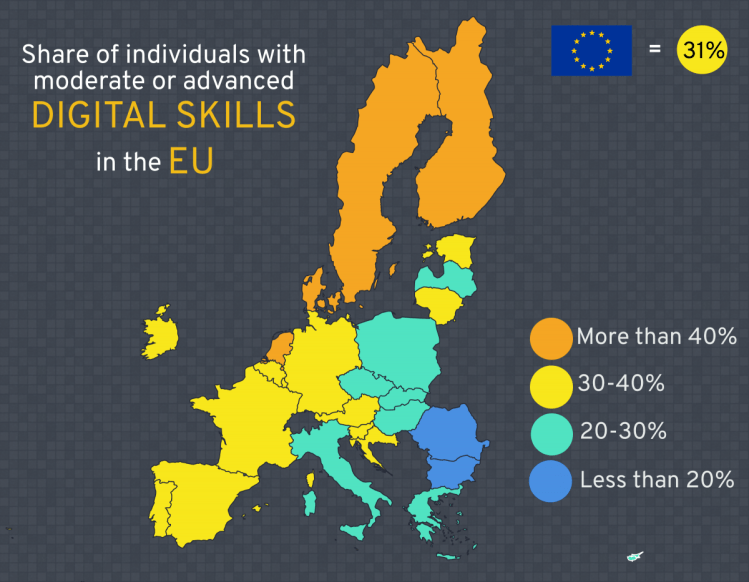

Only three out of 10 EU citizens had above basic digital skills in 2019([5]). This average masks a substantial “geographical” digital divide. In Member States in the north and west, digital skills are much better developed than in countries in the south and east. While half of Dutch, Finnish and Danish citizens had moderate or advanced digital skills, this is only the case for 1 out of 10 citizens in Romania and Bulgaria. In most countries the situation is improving ([6]). Citizens of some of the Baltic countries, Slovenia or Croatia already have levels of digital skills comparable to their counterparts in countries in the west (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Share of individuals (aged 16-74) with above basic digital skills in 2019

Source: Cedefop Skills Panorama, Digital skills use (https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/indicators/digital-skills-use), own calculations.

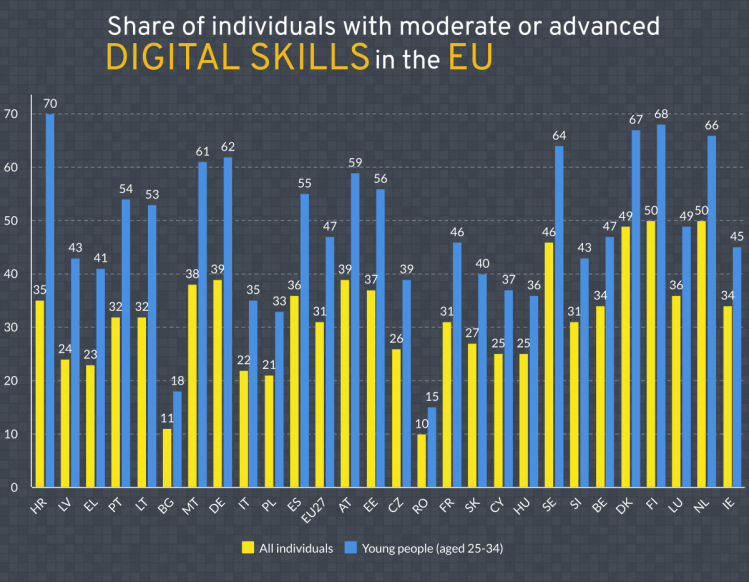

A digital divide also exists between different age groups. Unsurprisingly, young people tend to have much higher level of digital skills than the rest of the population (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Share of individuals with above basic digital skills in 2019 – young people (25-34) compared to population average (16-74)

Source: Skills Panorama, Digital skills use (https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/indicators/digital-skills-use), own calculations. Note: The ranking of countries is based on the difference between people and the population average.

In several countries with relatively well digitally-skilled populations such as Denmark, the Netherlands and Finland the age-driven digital divide is relatively modest. In countries on the left side of figure 3 the digital skills gap between young people (25-34 year olds) and the population as a whole is highest. In Croatia, Latvia and Greece, people over 34 likely not only have less developed digital skills than younger people, but also lack good access to training opportunities. With the level of digital skills among the young already relatively high, these countries could consider policies focusing on those over 34 years of age.

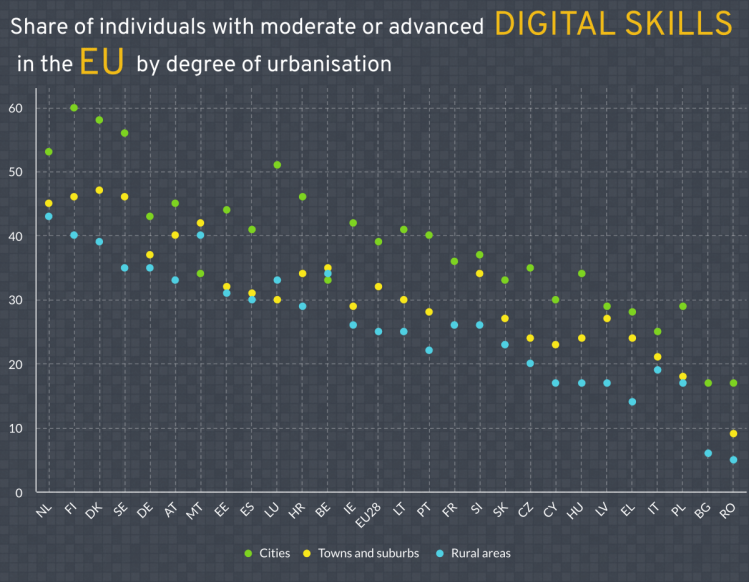

The degree of urbanisation gives rise to a third digital divide. Rural, but in many cases also suburban areas lag significantly behind metropolitan areas (see Figure 4). Eastern and southern EU Member States (Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia, Greece, Hungary) appear to be most affected by this challenge . With young people often leaving the rural areas they grew up in for cities, age and degree of urbanisation are mutually reinforcing factors shaping the digital divide.

Figure 4: Share of individuals with above basic digital skills in 2019 – by degree of urbanisation

Source: Eurostat. European Pillar of Social Rights / Data by degree of urbanisation. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/european-pillar-of-social-rights/indicators/data-by-degree-of-urbanisation

When it comes to more advanced ICT use, measured as the share of people creating digital content, the gap between cities and less populated areas is even larger. This suggests that apart from the digital skills divide, there are also significant rural/urban differences in terms of jobs available and their task content ([7]).

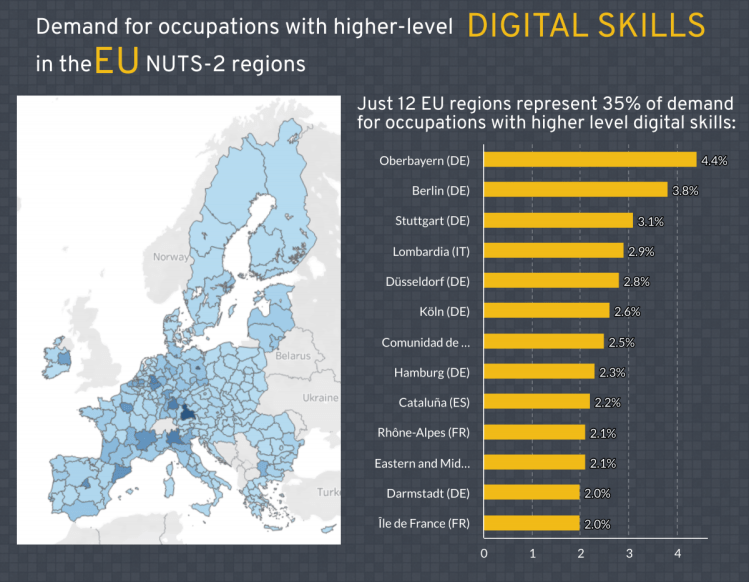

Cedefop’s Skills OVATE platform, which analyses online job advertisements, confirms this. Jobs requiring higher/advanced level digital skills (developing digital content, ICT safety and problem solving) such as ICT specialists, researchers & engineers, office professionals or some clerical occupations are concentrated in urban areas. More than a third of online job ads for these occupations is concentrated in just 12 (out of 281 EU NUTS-2 regions) mostly urban regions (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Demand for occupations with advanced digital skills by NUTS-2 region (2020)

Source: Cedefop Skills OVATE. Own calculations. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-visualisations/skills-online-vacancies (data collected between July 2018 and June 2020). Note: Darker colours in the map indicate a higher share on total demand across regions.

Digital skills in occupations

Already before the Covid-19 pandemic hit and remote work really took off, demand for digital skills was high. Apart from the ICT sector, also the finance, business administration, science & engineering, education, health care, trade, and manufacturing have experienced rapid digital transformation ([8]).

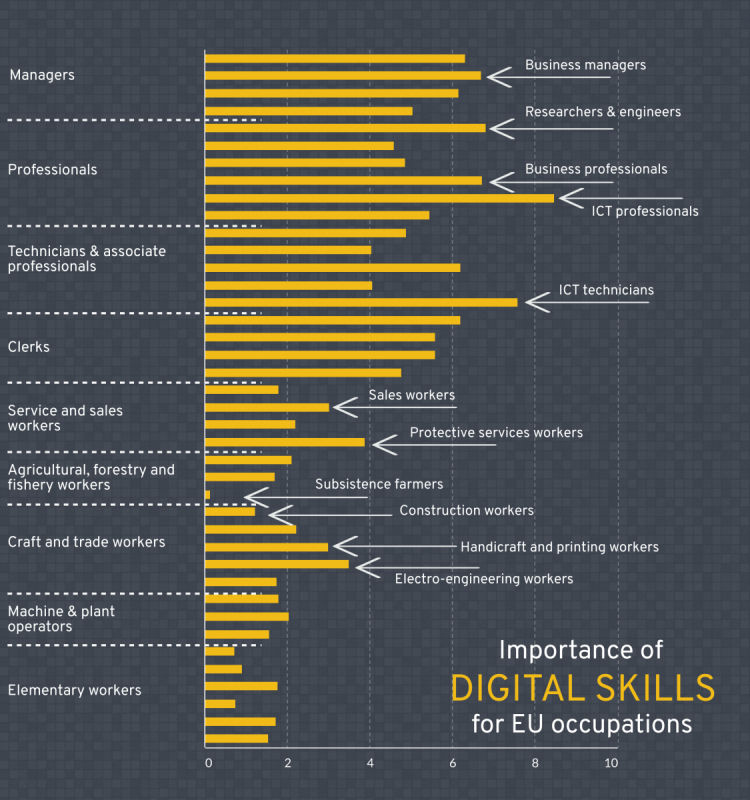

Although the nature of skills needed varies, digital skills are important for most managerial, professional, associate professional and even clerical jobs ([9]). While most medium to low skilled occupations (e.g., most elementary and factory jobs, subsistence farmers and construction workers)only require basic digital skills there are exceptions. Protective services workers, handicraft and printing workers, electro-engineering workers and sales workers require a higher digital skills level to do their job (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Use of ICT in occupations (ISCO 1 and 2)

Source: Tasks within occupation indicator, Cedefop Skills Panorama (2020) https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/indicators/tasks-within-occupationNote: For each occupation at the 2-digit ISCO code level, it measures task content (what people do at work) and methods and tools used (how work is organised and done). Ranging from 0 to 10, the indicator measures to which degree an occupation requires the use of a computer, internet, e-mails, spreadsheets, word processor, programming languages and the level of computer use needed.

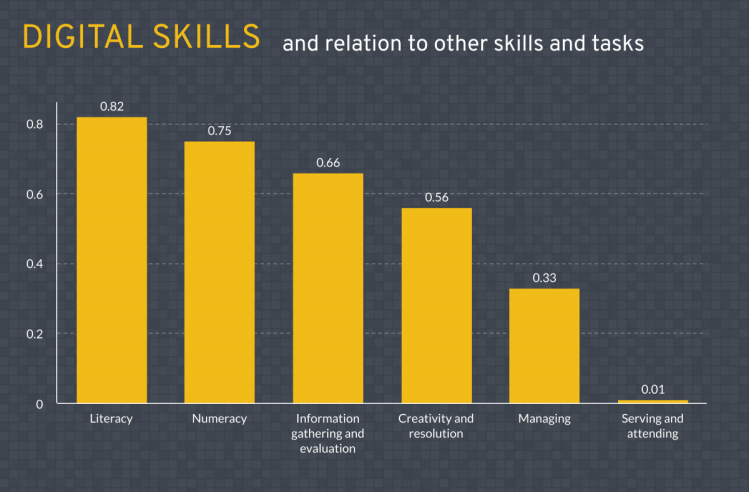

Other types of work tasks are linked to ICT tasks (Figure 7). With ICT use strongly linked to literacy (i.e., the manipulation of verbal information) and numeracy (i.e., the manipulation of numerical information), ICT intensive occupations are also strongly dependent on information processing. Similarly, use of ICT commonly goes hand in hand with problem-solving, proxied here by information gathering & evaluation and by creativity & resolution. In occupations with high ICT use, social tasks appear to be less important. However, the link between ICT use and serving or attending others (social tasks) depends on the particular occupation. Some occupations (e.g., production and specialised services managers) extensively use ICT for attending others, while this is not the case in others (e.g., personal care workers). The relation between ICT use and management tasks – while positive – is relatively weak. This suggests managing and coordinating others typically requires only up to medium-level digital skills.

Figure 7: Relationship between ICT use and other skills and tasks

Source: Tasks within occupation indicator, Cedefop Skills Panorama (2020). Own calculations. https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/indicators/tasks-within-occupation Note: 0-1 scale where values close to zero indicate weak linkage while values close to 1 indicate close linkage to digital skills.

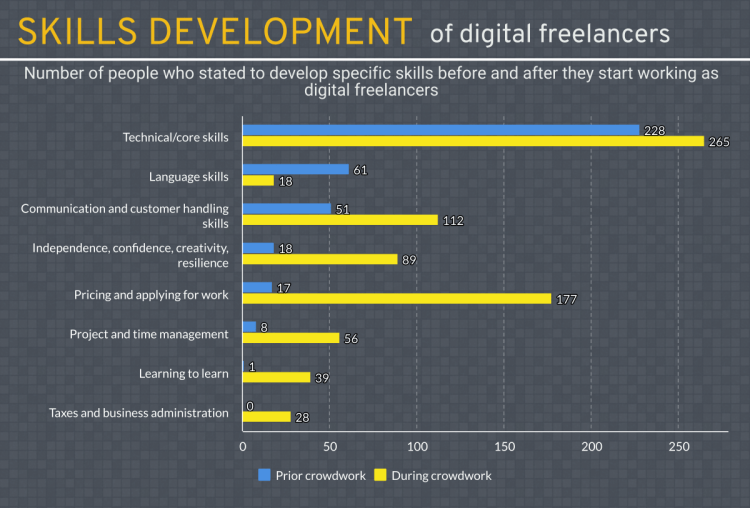

The rise of digital freelancers or platform workers showcases how digital environments and skills influence the way people work. Matching skills demand and supply in ways very different from the conventional job vacancy approach, companies and organisations use specialised web portals to advertise tasks. Workers with different skills sets compete for those. Digital skills apart from being an enabler in the matching process, are also important in many of the tasks on offer. However, simply mastering digital skills only is not sufficient for success. Cedefop’s Crowdlearn survey among platform workers shows ([10]) technical and digital skills are most important before joining a platform and remain so even after some time working via that platform. But skills acquisition is faster paced in other areas: communication and customer handling; independence, confidence, creativity and resilience; pricing and applying for work; project and time management and ability to learn (Figure 8).

Mastering digital skills goes hand in hand with mastering other advanced, usually transversal skills. These links are becoming more important in the uncertain and fluid current context and the post Covid-19 labour market.

Figure 8: Skills development among digital freelancers

Source: Developing and matching skills in the online platform economy. Cedefop 2020. Available at: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/3085

Digital skills in online job advertisements

Box 1: Cedefop research on online job advertisements

The analysis of demand for digital skills is based on Cedefop’s Skills OVATE, a system for analysing online job advertisements. While for many other skills and occupations this type of labour market information may not be the most representative one, for digital skills and jobs online job ads are a suitable and comprehensive source, recording most jobs on offer.

Cedefop Skills OVATE uses the European multilingual classification of Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO). ESCO distinguishes between skills and knowledge; skills are defined as “the ability to apply knowledge and use know-how to complete tasks and solve problems”, while knowledge is understood as “the outcome of the assimilation of information through learning”.

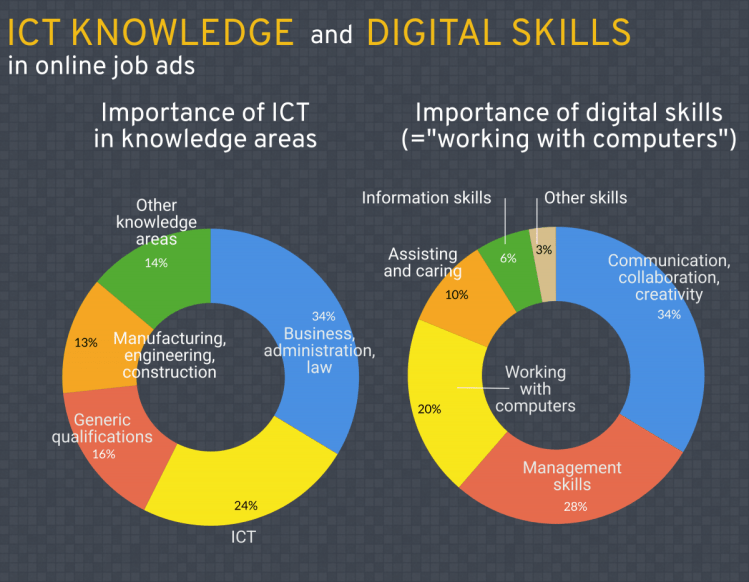

ICT knowledge and digital skills are among the most important assets requested in online job advertisements. Roughly one in every four knowledge areas requested relates to ICT and one in five skills requested is a digital one (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: ICT knowledge and digital skills requested in online job advertisements

Source: Cedefop Skills OVATE. Own calculations. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-visualisations/skills-online-vacancies (data collected between July 2018 and September 2020)

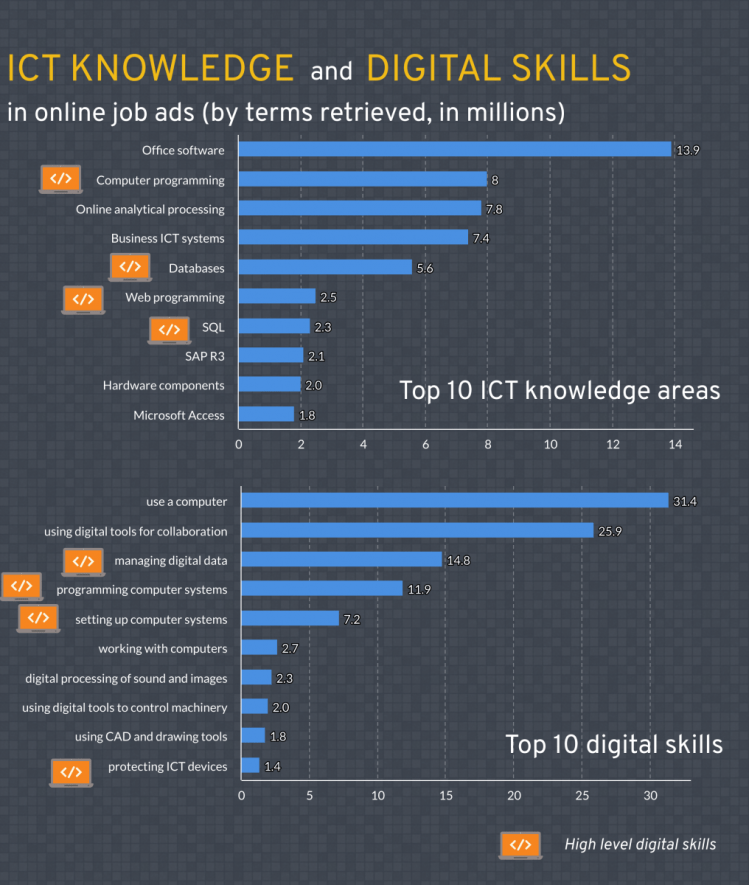

ICT knowledge areas and digital skills indicating the use of ICT (such as computer use; use of office software or using digital tools for collaboration) in the EU dominate skills demand across occupations and sectors (Figure 10).

Figure 10: ICT knowledge areas and digital skills most requested in online job advertisements

Source: Cedefop Skills OVATE. Own calculations. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-visualisations/skills-online-vacancies (data collected between July 2018 till June 2020)

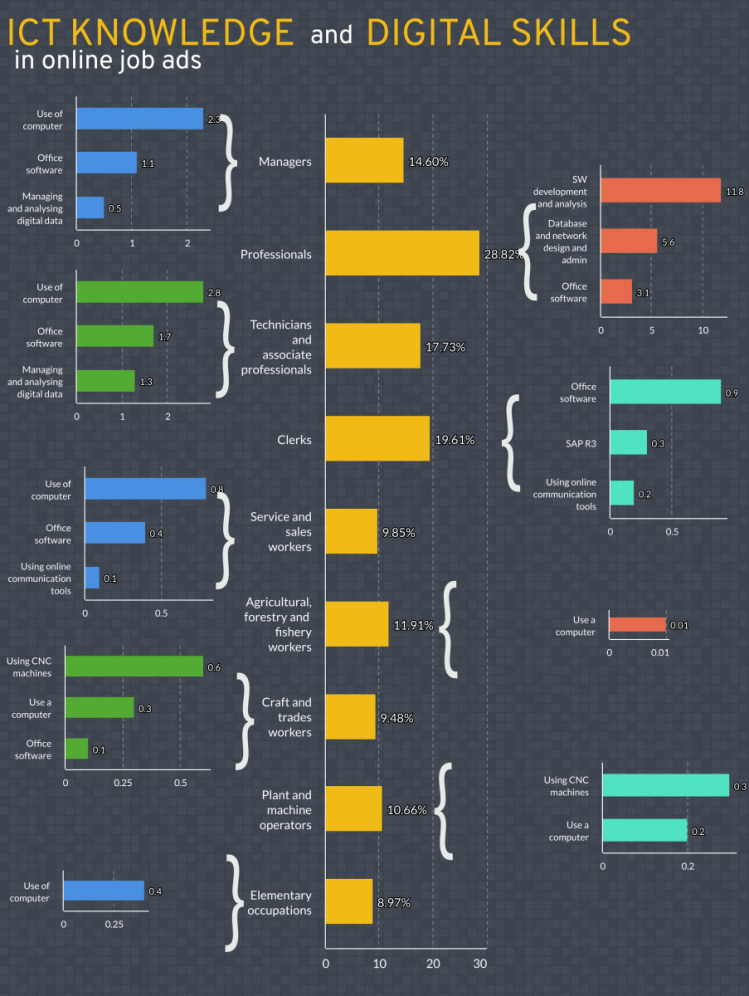

Unsurprisingly, the nature of digital skills demand is closely linked to occupation (Figure 11). ICT knowledge areas and digital skills are most requested in job advertisements for professionals, where on average about 3 out of every 10 skills requested is a digital skill. Using this metric, with almost 20%, job ads for clerical work – an occupation transformed as a result of digitalising administrative procedures – rank second.

Figure 11: Average share of ICT knowledge and digital skills in total number of skills and knowledge areas requested in online job ads by broad occupation (ISCO-1)

Source: Cedefop Skills OVATE. Own calculations. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-visualisations/skills-online-vacancies (data collected between July 2018 till June 2020)

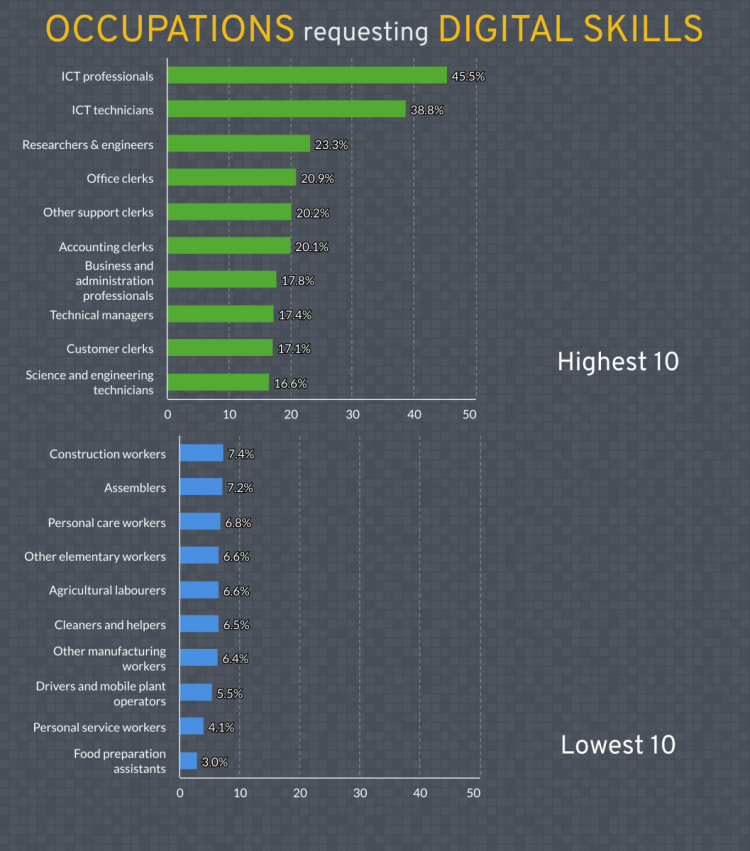

ICT knowledge and digital skills are most requested from ICT professionals and ICT technicians (Figure 12). Differences in the digital skills content of other professional, managerial and clerical occupations are relatively small. Elementary workers, factory workers and people providing personal services rely comparatively much less on digital skills.

Figure 12: Average share of digital skills and knowledge in total skill demand requested in online job ads by detailed occupation (ISCO-2)

Source: Cedefop Skills OVATE. Own calculations. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-visualisations/skills-online-vacancies (data collected between July 2018 till June 2020)

Trends in digital skills demand

ICT specialists

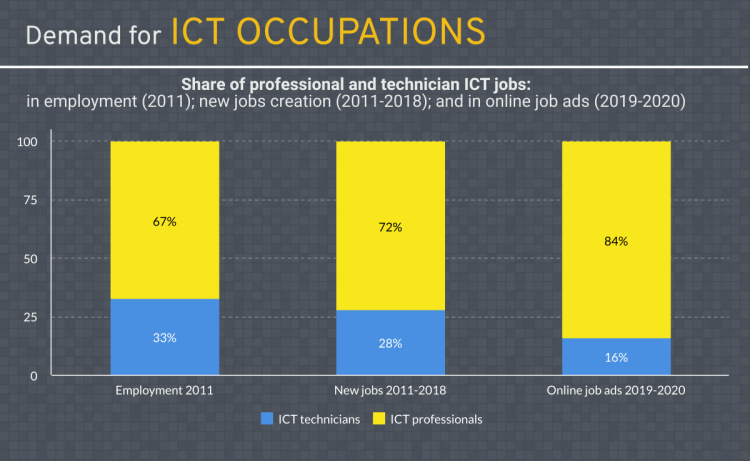

The profile of ICT specialists is changing. While demand for ICT professionals is rising, the employment share of ICT technicians is declining. Although there was job creation in both occupations since 2011, the share ICT technicians in total demand for ICT specialists is shinking. In 2011, out of every 3 ICT specialist jobs, one was a job for an ICT technician. Of the over 1.6 million new ICT specialist jobs created in 2011-18, 1 in 4 concerned ICT technicians. And according to Cedefop’s Skills OVATE, since the beginning of 2019 only one in every six job ads for ICT specialists was for an ICT technician (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Employment, job creation and online job ads for ICT specialists

Source: Cedefop Skills OVATE and Skills Panorama. Own calculations.

The observed shift may be linked to several trends. Advancements in artificial intelligence, cloud-based services and most of all use of mobile devices have polarised demand for ICT skills. While demand for ICT specialists has increased, technicians are less needed as even sophisticated ICT tools can be now be mastered and administrated by people with user-level skills. In addition, many ICT technicians have progressed to ICT professional level, because growing demand for such profiles incentivised them to make a career move.

Covid-19 and digital skills

The Covid-19 pandemic and its wide-ranging impacts have accelerated digital skills demand in many occupations, especially non-ICT ones. Effective use of digital skills proved to be a driver of resilience. They help workers and entire organisations adapt to the new realities the pandemic has shaped. Particularly in retail and service sectors, where it is difficult to deliver products and services remotely, digital skills can spur the transformation of business models and help avoid lay-offs and bankruptcies. Digital skills also enabled continued provision of public and private services. Thanks to them, many workers for whom digital skills were not critical before the pandemic (for example teachers, clerical and other office jobs), could shift to remote working basically overnight.

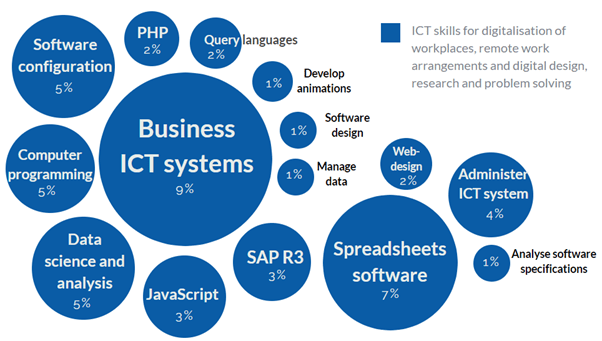

The growing importance of digital skills and knowledge in online job advertisements in the course of 2020 is a sign of progressing workplace digitalisation. Demand for knowledge of business ICT systems and applications, tools for software and web development and configuration and for data analysis accounted for roughly half of the growth in skills demand (see figure 14). And many of them are requested across a range of occupations, not just for ICT specialists.

Figure 14: Share of digital skills in skills growing in demand in 2020

Source: Cedefop: Coronavirus and the European job market: how the pandemic is reshaping skills demand. Available at: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/coronavirus-and-european-job-market-how-pandemic-reshaping-skills-demand

In some occupations and economic sectors, such as food & accommodation, wholesale & retail trade or arts & recreation, digitalisation and remote work are a less straightforward option ([11]). There, the majority of jobs requires substantial personal interaction and only limited ICT skills. Albeit slower, transformation in these sectors is ongoing: companies are developing solutions to protect their sales workers, attendants, receptionists, waiters or cashiers. Creative and smart application of digital technologies mitigates the impact of lockdowns and social distancing measures.

According to Cedefop, in tourism (of which accommodation & food is a key part) provision of services remotely such as hotel check-ins, food ordering or ticket sales, is expanding. Arts & recreation providers apply similar approaches, including virtual tours and exhibitions. As a result of the rapid digitalisation in retail, the expansion of e-commerce in a few months equalled what had been forecasted (pre Covid-19) for the next 5 years ([12]). Skill demand changed in response, as the new normal suddenly required more back office staff dealing with online orders and more people in packaging and delivery services. It is indicative that during lockdown, 28% of Europeans shopped for groceries online, up from 18% before the pandemic ([13]).

These changes, once ingrained into organisations’ business models and customer behaviour, may become permanent, even after the pandemic subsides. And while some jobs unaffected by digital technologies will remain, digitalisation will continue to shape skills, tasks and jobs.

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Discussion

No comments yet.