“Over the last two decades, high – and, in some countries, rising – rates of low-wage work have emerged as a major political concern” writes John Schmitt in Low-wage Lessons (Choosen excerpts by Job Market Monitor to follow)

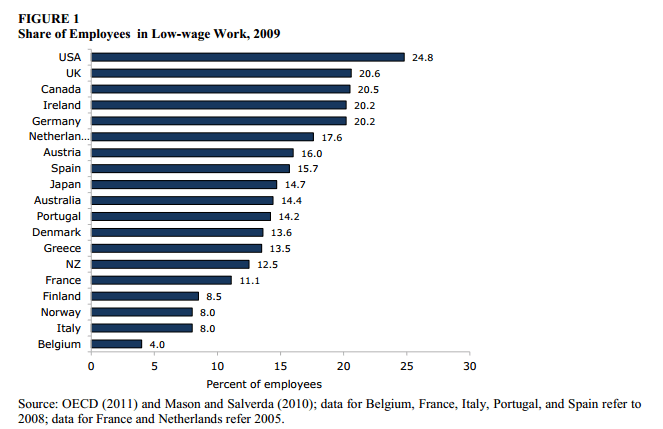

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in 2009, about one-fourth of U.S. workers were in low-wage jobs, defined as earning less than two-thirds of the national median hourly wage (see Figure 1). About one-fifth of workers in the United Kingdom, Canada, Ireland, and Germany were receiving low wages by the same definition. In all but a handful of the rich OECD countries, more than 10 percent of the workforce was in a low-wage job.

If low-wage jobs act as a stepping stone to higher-paying work, then even a relatively high share of low-wage work may not be a serious social problem. If, however, as appears to be the case in much of the wealthy world, low-wage work is a persistent and recurring state for many workers, then lowwages may contribute to broader income and wealth inequality and constitute a threat to social cohesion.

The report draws five lessons on low-wage work from the recent experiences of the United States and other rich economies in the OECD.

The lessons

Lesson 1: Economic Growth is not a Solution to the Problem of Low-wage Work

Lesson 2: More “Inclusive” Labor-market Institutions Lead to Lower Levels of Low-wage Work

Lesson 3: The United States is a Poor Model for Combating Low-wage Work

Lesson 3A: The U.S. Minimum Wage is Set Too Low to Reduce the Share of Low-wage Work

Lesson 3B: The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) has Contradictory Effects on the Volume of Low-wage Work and on the Well-being of Low-wage Workers

Lesson 4: Low-wage Work is Not a Clear-cut Stepping Stone to Higher-wage Work

Lesson 5: In the United States, Low Wages are among the Least of the Problems Facing Low-wage Workers

The experience of the last few decades suggests that we have a pretty good idea of how to reduce the size of the low-wage workforce. “Inclusive” labor-market institutions that extend the pay, benefits, and working conditions negotiated by workers with significant bargaining power to workers with less bargaining power appear to be the most effective general remedy for low-wage work. The specifics can take many forms, from extending collective bargaining agreements to cover workers who are not themselves members of unions, to setting a minimum wage at or near the threshold for low-wage work. Greater public social spending may be another way to increase the “inclusiveness” of national industrial relations systems since a generous social safety net improves the bargaining position of low-wage workers relative to their employers. The national details aside, the available cross-country data show a strong association between higher levels of inclusiveness and lower levels of low-wage work.

The United States, as one of the least “inclusive” OECD countries, primarily offers cautionary lessons when it comes to low-wage work. Union coverage rates in the United States are the lowest among comparable OECD economies, providing little in the way of protections for the large majority of low-wage workers. In principle, federal and state minimum wage laws and federal and state EITC programs could significantly lower the incidence of low-wage work. But, in practice, wage floors and EITC payments in the United States have been set too low to prevent a long-term

increase in low-wage work, let alone reduce the ranks of the already sizable sector.

For some workers, low-wage work is a stepping stone to better things. For an important share of low-wage workers, however, a low-paid job is not much better than unemployment and can even harm their long-term wage and employment prospects. Policy discussions often rightly emphasize the importance of a job, any job, in the fight against poverty (particularly in contexts where national benefit systems are not generous enough to raise jobless families out of poverty). But, the relatively low levels of mobility out of low-wage work argue against seeing an expansion of low-wage employment as a straightforward solution to the problems of poverty or wage inequality.

In the United States, in particular, low wages are only the most obvious problem facing low-wage workers. In the absence of legal or contractual guarantees, low-wage workers in the United States are far less likely to have health insurance (private or public), paid sick days, paid family leave, paid vacation and holidays, and other benefits that are more routinely provided to higher-wage workers (and to low-wage workers in other rich economies). Raising wages at the bottom – without other

measures to address the terms and conditions of low-wage employment – will do little or nothing to address these other pressing concerns facing low-wage workers.

Full Report @

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: US / Unemployment Insurance: Extended benefits have added more than 125 percent over the past two years « Job Market Monitor - January 16, 2013

Pingback: US / 47.5 million in Working Poors Families, could reach 50 millions soon « Job Market Monitor - January 16, 2013

Pingback: US / Means-tested programs and tax credits for low-income households rose more than tenfold in the four decades since 1972 « Job Market Monitor - February 11, 2013

Pingback: Low-Wage / Wal-Mart vs. the Feds: Who’s the King? | Job Market Monitor - May 14, 2013